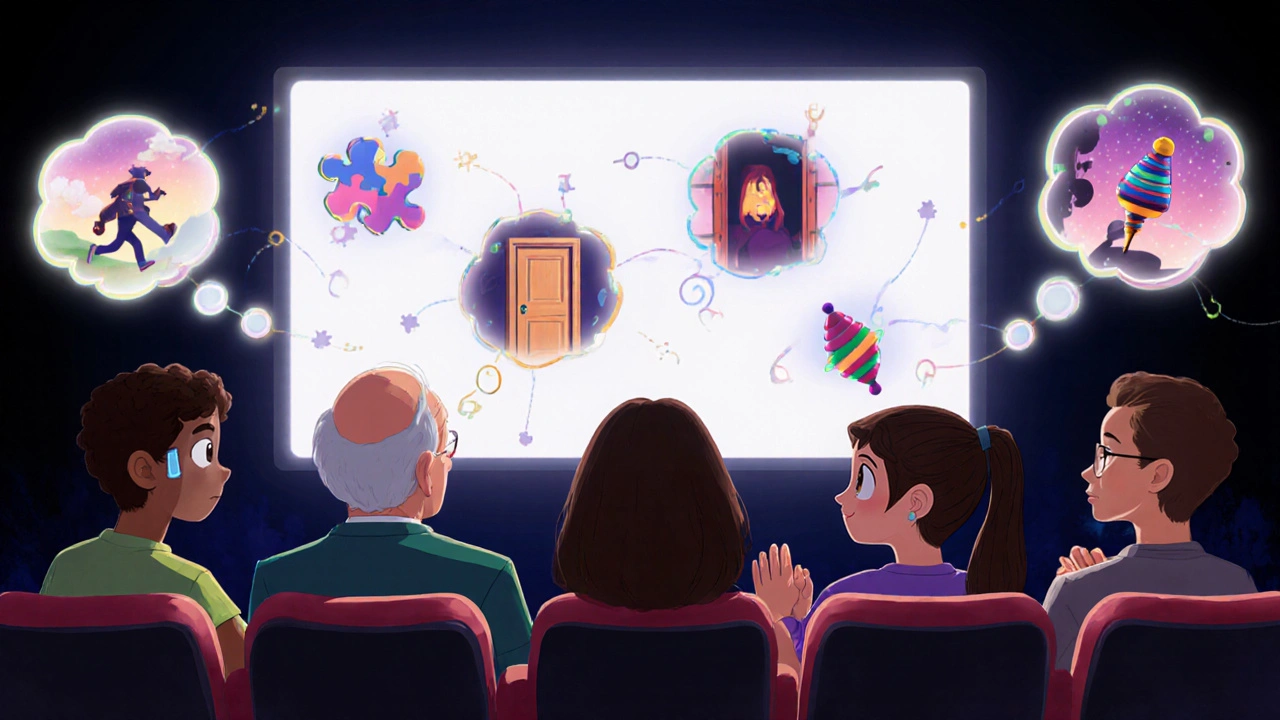

Have you ever watched a movie and felt your heart race during a chase scene-even though you knew it was all fake? Or cried at a character’s goodbye, even though you never met them? That’s not magic. It’s your brain at work. Cognitive film theory explains exactly how that happens-not through hidden symbols or unconscious desires, but through the way your mind naturally processes what you see and hear on screen.

Why Your Brain Loves Movies

Cognitive film theory emerged in the 1980s as a direct challenge to the dominant film theories of the time. Back then, scholars like Christian Metz and Laura Mulvey argued that films operated like dreams-encoding hidden meanings, reinforcing ideology, and manipulating viewers through unconscious forces. But cognitive theorists said: wait a minute. What if viewers aren’t passive puppets? What if they’re active problem-solvers? David Bordwell, Noel Carroll, and Carl Plantinga started asking real questions: How do people follow a complex timeline like in Inception? Why do we feel for characters we know aren’t real? How do quick cuts and matching angles make a scene feel seamless? Their answers came from psychology, neuroscience, and perception science-not literary theory or philosophy. The core idea is simple: your brain doesn’t just receive images. It builds them. When you watch a film, your mind fills in gaps, predicts outcomes, and connects dots based on past experiences. This isn’t guesswork-it’s a universal mental process. You don’t need to be educated to understand a chase scene. You just need to have lived.How You Build a Story in Your Head

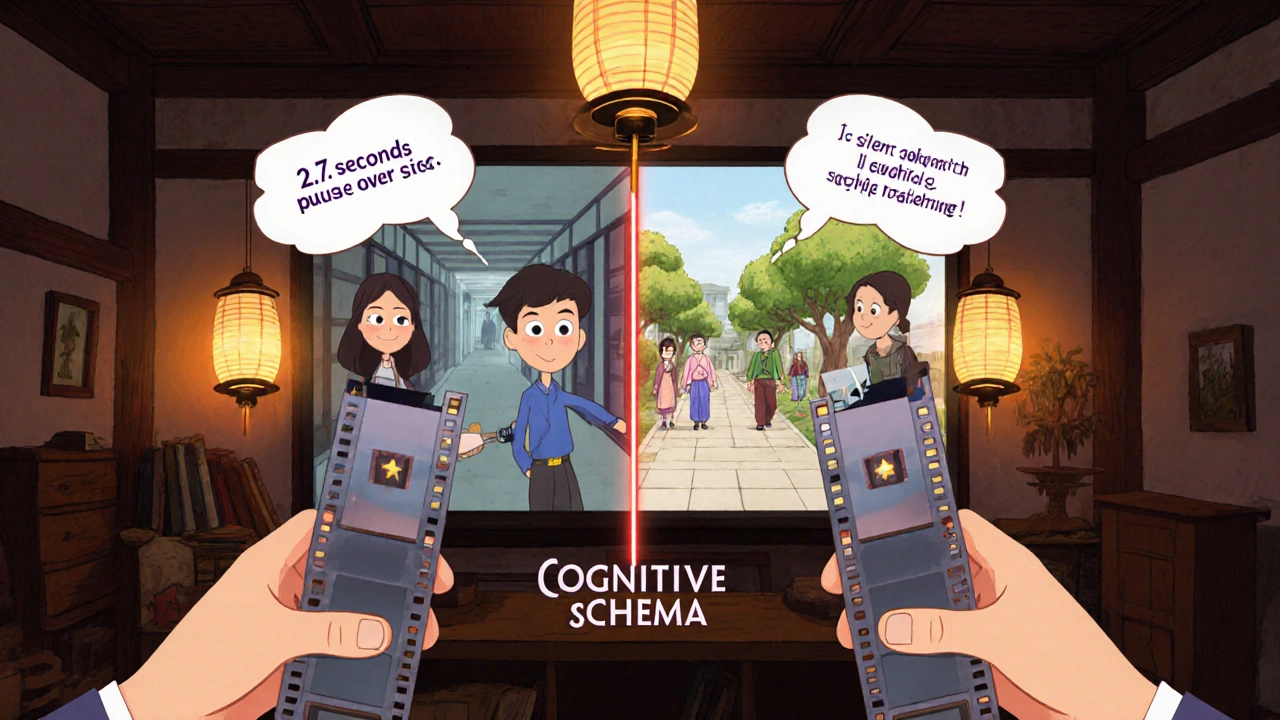

Films don’t hand you a story. They give you fragments-shots, sounds, edits-and your brain stitches them together into something called the fabula, or the full story. The actual images on screen? That’s the syuzhet: the order they’re presented in. Think of it like a jigsaw puzzle. You don’t see the whole picture at once. You pick up pieces: a hand reaching for a door, a shadow moving behind it, a scream. Your brain uses what you already know-how doors work, how shadows move, what screams mean-to construct the full event. That’s schema theory in action. Your mind pulls from stored knowledge to make sense of new input. This is why continuity editing works. The 180-degree rule? It’s not a Hollywood tradition-it’s a cognitive necessity. Crossing the line confuses your brain because it breaks spatial logic. Shot-reverse-shot? That’s how we naturally take turns in conversation. Your brain expects it. When filmmakers respect those patterns, you don’t notice them. When they break them, you feel it-even if you can’t explain why.Emotions Aren’t Fake, Even If the Characters Are

Here’s the big surprise: you feel real emotions for fictional people. Carl Plantinga called this the paradox of fiction. How can you be sad for a character who doesn’t exist? Cognitive theory says: because your brain doesn’t fully separate imagination from reality when processing emotion. When you see a character cry, your mirror neurons fire as if you were crying too. When they run, your motor cortex lights up as if you were running. Studies using fMRI show that viewers’ brains activate the same areas when watching someone grasp a cup as when they themselves grasp one. Plantinga identified three types of emotional responses:- Global affect: Immediate, visceral reactions-like jumping at a jump scare.

- Acknowledged fiction: You know it’s fake, but you still feel it-like sadness at the end of Up.

- Empathy: You emotionally align with a character’s goals and struggles. That’s why you root for Max Rockatansky in Mad Max: Fury Road, even though he barely speaks.

Why Some Films Feel ‘Right’ and Others Don’t

Not all films are created equal in how they engage the mind. A film like 2001: A Space Odyssey uses silence, long takes, and abstract imagery to trigger deep cognitive and emotional responses. The use of Ligeti’s ‘Requiem’ during the Star Gate sequence isn’t just atmospheric-it’s designed to disrupt normal perception. Studies show viewers’ heart rates spike by an average of 22 beats per minute during that sequence. On the other hand, a poorly edited action scene can feel chaotic because it violates spatial logic. If the camera jumps around without clear direction, your brain gets overloaded. You stop following the story-not because it’s boring, but because it’s confusing. This is why editing matters more than you think. The 3-second rule-keeping shots under three seconds for fast-paced scenes-isn’t arbitrary. It matches the average human attention span for processing visual motion. Too long, and you lose engagement. Too short, and you miss emotional weight.The Limits of Cognitive Theory

Cognitive film theory is powerful-but it’s not perfect. Its biggest weakness? It often ignores culture. A Western viewer might focus on the main character in a scene. An East Asian viewer, according to a 2023 study in Cognitive Science, is 18% more likely to notice the environment, the background, the relationships between people. That’s not a mistake-it’s a difference in how culture shapes perception. Critics like David Rodowick and Mary Ann Doane argue that cognitive theory treats viewers as universal machines, ignoring how race, gender, and power affect how we see films. For example, Do the Right Thing doesn’t just tell a story-it demands a cultural context. Cognitive theory can explain how you follow the plot, but not why you might feel anger, guilt, or silence in response to it. That’s why newer research is blending cognitive theory with cultural analysis. Greg Smith and others now study how cultural schemas-shared beliefs about family, justice, or heroism-influence how people interpret films. It’s not about replacing cognitive theory. It’s about expanding it.

What This Means for Filmmakers and Viewers

For filmmakers, cognitive theory isn’t just academic. It’s practical. It tells you how to hold attention, when to cut, where to place a character’s face, how long to linger on silence. The rise of neurocinema-using EEG and eye-tracking to test audience responses-means studios are now testing emotional impact before release. A 2021 study of A Quiet Place found viewers had 42% greater brain activity during silent scenes than dialogue-heavy ones. That changed how horror films are edited. For viewers, it’s even simpler. You don’t need to know the theory to enjoy a film. But knowing it helps you understand why you react the way you do. Why you gasped. Why you cried. Why you looked away. It turns passive watching into active understanding. And that’s the real gift of cognitive film theory: it doesn’t make films more mysterious. It makes them more human.Where to Go Next

If you want to dig deeper, start with Bordwell and Thompson’s Film Art: An Introduction. It’s the clearest entry point. Then read Plantinga’s Moving Viewers for emotion. For the neuroscience side, check out The Empathic Screen by Gallese and Guerra. You’ll find that the most powerful films don’t rely on complex metaphors. They rely on basic human instincts-how we see, how we feel, how we connect. That’s not just theory. That’s truth.What is cognitive film theory?

Cognitive film theory is a framework that studies how viewers actively use perception, memory, and emotion to understand and respond to films. Unlike older theories that saw audiences as passive, it treats viewers as problem-solvers who build meaning from what they see, using universal mental processes like schema formation and empathy.

How do viewers follow complex stories like in Inception?

Viewers follow complex narratives through consistent spatial and temporal cues. Even with multiple layers, films like Inception use visual anchors-like the spinning top or character costumes-to help the brain track reality shifts. Continuity editing and recurring motifs reduce cognitive load, letting viewers focus on emotional stakes rather than confusion.

Why do we cry at fictional characters?

We cry because our brains simulate the emotions we see. Mirror neurons activate when we watch characters act, creating a physical and emotional response even though we know it’s not real. This is called embodied simulation. You don’t need to believe the character exists-you just need to recognize their emotion as something you’ve felt before.

Is cognitive film theory scientific?

Yes. Unlike psychoanalytic or semiotic theories, cognitive film theory uses empirical methods: eye-tracking, fMRI scans, heart rate monitoring, and behavioral studies. Researchers measure actual viewer responses, not just interpretations. This makes it testable, repeatable, and grounded in psychology and neuroscience.

Does cognitive theory ignore culture?

Early versions did. But modern cognitive film theory now includes cultural schemas-how upbringing and society shape how we interpret stories. For example, East Asian viewers tend to focus more on context and relationships, while Western viewers focus on individual characters. The theory is evolving to account for these differences without losing its core focus on universal mental processes.

How is this used in real filmmaking?

Studios like Pixar use cognitive principles to time emotional beats. Eye-tracking data shows viewers fixate on faces for about 2.7 seconds during emotional moments, so close-ups are held longer. Silence in horror films triggers stronger brain activity than dialogue, influencing editing. Neurocinema labs now test audience responses before release to optimize pacing and emotional impact.

What’s the difference between cognitive theory and psychoanalytic theory?

Psychoanalytic theory says films reveal hidden desires and unconscious fears-often tied to Freud or Lacan. Cognitive theory says viewers actively construct meaning using everyday mental tools like memory, attention, and pattern recognition. One looks inward to the psyche; the other looks outward to perception and cognition.

Can cognitive theory explain why some films feel boring?

Yes. If a film violates basic perceptual rules-like inconsistent screen direction, unclear spatial relationships, or mismatched sound-it forces the brain to work too hard. Instead of being absorbed, viewers become distracted. Boredom often comes from cognitive overload, not lack of plot. Good films make thinking feel effortless.