When a podcast like Serial or The Daily blows up, it doesn’t just stop at ears. People want to see it. They want to feel the weight of the story in their bones, not just hear it in their headphones. That’s why so many audio investigations are now becoming documentaries. But turning a 10-episode podcast into a 90-minute film isn’t just about slapping visuals on voice clips. It’s a full rewrite. A reshaping. A reinvention.

Start with the core question the podcast asked

Most great podcasts are built around one stubborn, unanswered question. Was Adnan Syed guilty? Who really killed Tara Calico? Why did the factory close without warning? That question is your documentary’s spine. If your podcast had five episodes exploring different angles, your film needs to cut through the noise and focus on the one thread that still makes viewers lean forward in their seats.Take Dirty Money on Netflix. It started as a series of investigative reports from podcast producers. The filmmakers didn’t try to cover every scandal. They picked the one where the human cost was clearest-the corporate fraud that left elderly people without insulin. That became the emotional anchor. Your documentary should do the same. Find the moment where the story stopped being about facts and started being about people.

Visuals aren’t decoration-they’re evidence

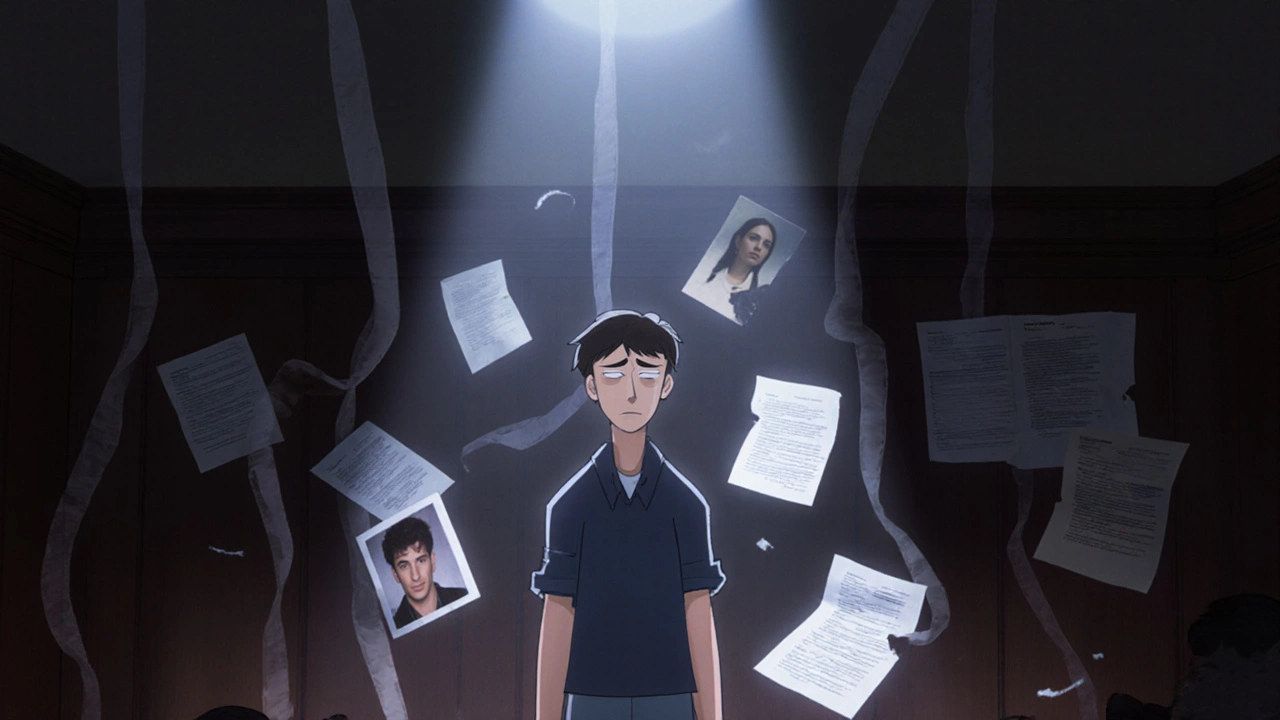

Podcasts thrive on imagination. You hear footsteps on gravel. You picture a shadowy figure in a parking lot. But film can’t rely on what the listener imagines. It needs proof. Real places. Real documents. Real faces.One documentary team adapting the podcast Missing in America spent months tracking down the exact motel room where a woman vanished. They didn’t just film it. They got permission to shoot at 3 a.m. with no lights, using only the glow of a flickering neon sign. That’s the kind of detail that turns a podcast’s "maybe" into a film’s "this happened here."

Archival footage, court transcripts, police reports, old photos-all these become your new script. If your podcast had interviews with 12 people, your film might only use three. But those three need to be the ones who hold the keys: a whistleblower with original emails, a neighbor who saw the last person alive, a clerk who kept records no one else knew existed.

Structure changes. Always.

Podcasts are built for bingeing. They drag you in slowly. They drop clues over weeks. Documentaries need to grab you in the first 90 seconds.A common mistake is to follow the podcast’s episode order. That’s a trap. Episode 1 of your podcast might be background. Episode 2, the twist. Episode 5, the big reveal. But in a film, the twist needs to come before the third minute. The reveal by the 20th minute.

Try this: take your podcast’s biggest moment-the moment the host says, "We didn’t see this coming"-and put it at the start of the film. Then work backward. Show how you got there. Use flashbacks, voiceovers, and split screens to reconstruct the investigation. It’s not linear. It’s emotional. It’s urgent.

Look at The Tinder Swindler. The podcast version was a slow burn. The documentary opened with the victim sobbing on camera, saying, "I gave him everything." Then it rewound. That opening changed everything. Viewers didn’t just want to know what happened-they wanted to know how someone could believe it.

Sound design becomes your secret weapon

You can’t just mute the podcast audio and replace it with orchestral music. The original voices are your greatest asset. The hesitation in a witness’s voice. The shaky breath of someone recalling trauma. That’s gold.Use those audio clips as the foundation. Layer them under visuals. Let the viewer hear the voice while seeing the empty house where the interviewee lived. Let the silence between sentences hang longer than you think is comfortable. That’s what made Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes so chilling. The audio didn’t just support the images-it haunted them.

Don’t over-score. Too much music kills tension. A single cello note, a distant door closing, the hum of a refrigerator in an empty kitchen-those are the sounds that stick with people.

Find the one person who changes everything

Every great documentary has a single character who carries the weight of the story. In a podcast, you have multiple voices. In a film, you need one.That person doesn’t have to be the victim. Or the suspect. Or even the host. It could be the librarian who found the hidden file. The ex-wife who kept a box of letters. The janitor who heard the argument through the wall.

The team behind The Case Against Adnan Syed realized the real emotional core wasn’t Adnan-it was Jay, the friend who testified against him. He wasn’t a villain. He was confused. Terrified. He didn’t know what he was doing. The film focused on him. Not because he was guilty, but because he was the one who couldn’t unsee what he’d done. That’s the character who made viewers feel something beyond curiosity. They felt guilt.

Ask yourself: Who in this story has the most to lose by speaking? That’s your anchor.

Don’t try to be fair. Try to be honest

Podcasts often play both sides. "Here’s the prosecution’s argument. Here’s the defense." That works when listeners can pause, rewind, and think. Films don’t have that luxury. Viewers don’t have time to weigh both sides equally.That doesn’t mean lie. It means prioritize. If the evidence overwhelmingly points to one truth, show it. Don’t give equal time to a conspiracy theory that’s been debunked three times. That’s not balance. That’s false equivalence.

Look at Our Father, the documentary about a fertility doctor who used his own sperm on hundreds of patients. The podcast had interviews with 40 children. The film focused on two: one who spent years searching for her father, and one who never wanted to know. That contrast told the whole story. No need to interview the rest. The truth was in the silence between them.

What you leave out matters more than what you include

You’ll have hours of audio. Dozens of interviews. Hundreds of pages of notes. Your job isn’t to use it all. It’s to know what to cut.One documentary producer told me they had a 3-hour interview with a whistleblower. Only 17 seconds made the final cut. But those 17 seconds were the moment he broke down and said, "I didn’t think anyone would care." That’s the line that haunted audiences. The rest? Background noise.

Ask yourself: Does this moment make someone feel something? Or just know something? If it’s the latter, cut it. Documentaries don’t inform. They transform.

Test it before you finish

Screen your rough cut for people who never heard the podcast. If they’re confused, you’ve failed. If they’re angry, you’ve succeeded.One team tested their documentary adaptation of a podcast about a missing child. The first audience didn’t cry. They laughed. Why? Because the film was too slow. The pacing felt like a lecture. They cut 12 minutes. Added a single shot of the child’s bedroom, empty except for a half-finished Lego set. The next screening? People couldn’t speak after it ended.

Don’t test with fellow podcasters. Test with strangers. People who don’t know the names. Don’t care about the timeline. They just want to know: Why does this matter?

It’s not a remake. It’s a resurrection

A podcast is a voice in the dark. A documentary is a light turned on in a room you didn’t know was there. You’re not copying the podcast. You’re giving it a body.Some of the best adaptations-like Unbelievable (based on Serial’s "An Unbelievable Story of Rape")-don’t even use the original audio. They rebuild the story from scratch, using the same facts, but letting the visuals carry the emotion.

If you’re adapting your own podcast, don’t be afraid to let go. Let the film become its own thing. The story you told in 10 episodes? Now it’s a single, breathless hour. And if you do it right, people will watch it. And then they’ll talk about it. And then they’ll change something.