When you watch a movie, you don’t just see a man holding a gun-you feel tension. You don’t just hear a slow piano note-you sense loneliness. That’s not magic. It’s semiotics at work. Semiotics in cinema is the study of how images, sounds, colors, and even silence act as signs that carry meaning. It’s not about what’s on screen, but what it makes you think, feel, or believe. And it’s everywhere-in every shot, every cut, every chord.

What Exactly Is Semiotics in Film?

Semiotics comes from the Greek word semeion, meaning "sign." In film, a sign is anything that stands for something else. A red rose isn’t just a flower-it’s love. A shadow creeping across a wall isn’t just darkness-it’s danger. The film theorist Christian Metz, who shaped modern film semiotics in the 1970s, called cinema a "language without a language." It doesn’t have grammar rules like English or French, but it still communicates. How? Through visual and auditory signs that audiences learn to read over time.Unlike words, film signs are often "motivated"-they look or sound like what they mean. A photograph of a car is a car. A siren sound is a siren. That’s different from the word "car," which has no physical link to the vehicle. This makes film powerful. You don’t need to be told what a bloody knife means. Your brain connects the image to violence, fear, or death instantly.

Three Types of Signs in Movies

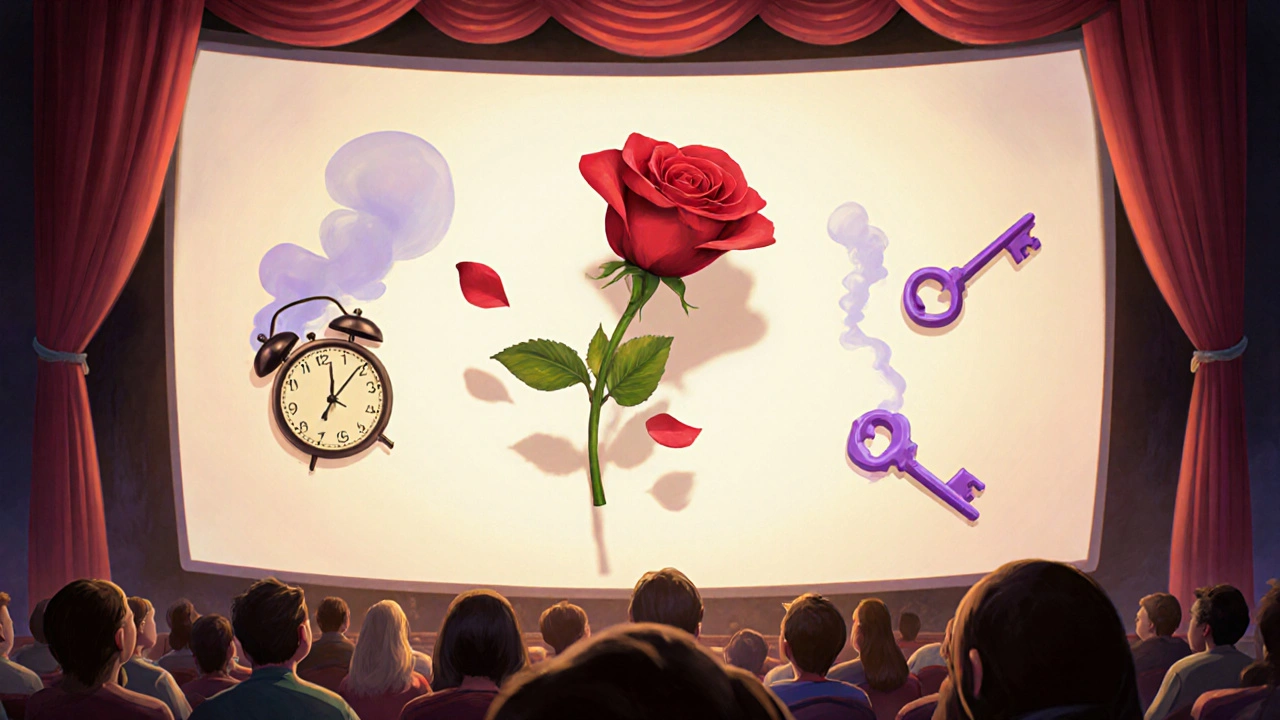

Film semiotics uses Charles S. Peirce’s system to break down signs into three types: iconic, indexical, and symbolic. Understanding these helps you see films differently.- Iconic signs look like what they represent. A close-up of a ticking clock means time is running out. A child’s drawing on the wall isn’t just art-it’s innocence or vulnerability. These signs work because of resemblance.

- Indexical signs have a direct, physical connection to what they mean. Smoke means fire. Footsteps in a hallway mean someone is approaching. A character’s trembling hands mean fear. These signs point to something real in the world, even if it’s not shown.

- Symbolic signs are arbitrary. They only mean something because culture says so. A white dress isn’t inherently pure-it’s symbolic of purity in Western culture. A black cat? Bad luck in some places, good luck in others. A red light in a film doesn’t just mean "stop"-it might mean danger, passion, or revolution, depending on context.

Think of The Grand Budapest Hotel. The pastel pink hotel? Iconic-it looks like a candy box. The repeated use of the same purple key? Symbolic-it stands for legacy and hidden history. The melancholic waltz music? Indexical-it echoes the rhythm of a fading world. You don’t need dialogue to understand the mood. The signs do the work.

Diegetic vs. Non-Diegetic: What Belongs in the World?

Not everything you hear or see in a film is part of the story world. That’s where diegetic and non-diegetic elements come in.- Diegetic elements exist inside the film’s reality. A character listens to a radio. A door slams. A conversation happens. These are part of the story’s world.

- Non-diegetic elements are outside the story. Background music, voice-over narration, text on screen-these are added for the audience, not the characters.

Think about Jaws. The iconic two-note theme? Non-diegetic. The shark isn’t hearing it. But it tells you: danger is near. That’s semiotics in action. The music doesn’t exist in the world of the film, but it controls how you feel. In contrast, when a character turns on a record player and a song plays-like "My Heart Will Go On" in Titanic-that’s diegetic. The characters hear it too. The meaning shifts depending on whether the sign is inside or outside the story.

How Shots Are Put Together: Syntagmatic and Paradigmatic Analysis

Semiotics doesn’t just look at single images. It looks at how they’re arranged. This is where two axes come in: syntagmatic and paradigmatic.- Syntagmatic is about order-how shots follow each other. A man looks off-screen, then a cut to a shadow moving behind a door. That sequence creates suspense. The meaning comes from the combination.

- Paradigmatic is about choice-why this shot and not another? Why a low angle instead of a high angle? Why red lighting instead of blue? These choices carry meaning. A low angle makes a character look powerful. A high angle makes them look weak. The director picked one. That’s intentional.

In Psycho, the famous shower scene uses rapid cuts (syntagmatic) to create chaos. But why those specific angles? Why the black-and-white? Why the screeching violins? Each choice is paradigmatic. Hitchcock could’ve used slow motion, color, or silence. He didn’t. And that decision tells you something about control, fear, and violation.

Codes: The Hidden Rules of Meaning

Films don’t communicate randomly. They follow codes-shared systems of meaning that audiences learn through culture and repetition.- Technical codes: Camera movement, lighting, color grading. A shaky camera means chaos. Warm lighting means safety or intimacy. Cold blue tones mean isolation or detachment.

- Social codes: How people dress, speak, move. A woman in a suit in a 1950s film? She’s breaking norms. A man in a trench coat? He’s probably a detective.

- Interpretative codes: Narrative expectations. If a character is introduced alone in a dark room, you assume they’re the protagonist-or the victim.

Look at Get Out. The sunken place? It’s a visual metaphor for systemic erasure. The teacup? A symbol of false hospitality. The deer on the road? An index of violence to come. These aren’t random. They’re built from cultural codes that audiences recognize-even if they don’t realize it. Jordan Peele didn’t invent them. He used them. And that’s why the film hits so hard.

Why Semiotics Still Matters Today

Some say semiotics is outdated-that it’s too academic, too rigid. But it’s not dying. It’s evolving.Streaming platforms like Netflix use semiotic patterns to guide your choices. The thumbnails you click? Designed with color, facial expressions, and composition to trigger curiosity or fear. The trailers? They follow the same sign systems as Hollywood films: quick cuts, intense music, a close-up of a character’s eyes. It’s not coincidence. It’s semiotics.

Even AI-generated films are being analyzed through semiotic lenses. Early tests show AI films use 34% fewer indexical signs-less smoke, fewer shadows, fewer physical traces of reality. That changes how we feel about them. They feel less real. Less human.

And in political films, semiotics reveals power. A leader shown from below, bathed in gold light? That’s not just cinematography. It’s a sign of authority. A protestor shown in silhouette? It’s a sign of anonymity, or invisibility. These aren’t accidents. They’re tools.

How to Start Reading Films Like a Semiotician

You don’t need a degree to see signs. Here’s how to begin:- Pause and describe. What do you actually see and hear? Don’t interpret yet. Just list: "A woman in a red coat walks down a wet street at night. Rain falls. A distant siren." That’s denotation.

- Ask: What kind of sign is this? Is the red coat iconic (it looks red)? Indexical (red = danger in this culture)? Symbolic (red = power, passion, warning)?

- Look at context. Why this shot? Why now? What came before? What comes after?

- Consider the code. Is this a horror film? Then shadows mean threat. Is it a romance? Then eye contact means connection.

- Question the choice. Why not a blue coat? Why not silence? Every decision is a message.

Try it with a scene from Blade Runner 2049. The orange dust storm? Iconic-it looks like fire. Indexical-it’s caused by environmental collapse. Symbolic-it’s the decay of the future. The low, rumbling score? Non-diegetic. It doesn’t come from the world. But it tells you: this is a world that’s dying. You didn’t need a narrator. The signs told you everything.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Semiotics can feel overwhelming. Here’s what trips people up:- Over-interpreting. Not every shadow is a metaphor. Sometimes a gun is just a gun. Use the "hierarchy of codes"-focus on the strongest, most repeated signs.

- Ignoring culture. A smile doesn’t mean happiness everywhere. In some cultures, it masks discomfort. Semiotics must account for context.

- Forgetting the viewer. Meaning isn’t fixed. A film can mean different things to different people. Semiotics gives you tools to decode the text-but the audience completes the meaning.

The best semiotic analysis doesn’t claim to have the "right" answer. It shows how meaning is built-and how easily it can be undone.

Is semiotics still relevant in today’s films?

Yes. While newer theories focus on viewer psychology or cultural identity, semiotics remains the most reliable method for decoding how meaning is built into the film itself. It’s used in advertising, political media, streaming interfaces, and AI-generated content. In 2023, 67% of film schools still teach it as a core tool. It’s not the only way to analyze film-but it’s the most systematic.

Can you analyze a film without knowing semiotics?

Absolutely. People have been moved by films for over a century without ever hearing the word "semiotics." But knowing semiotics changes how you watch. You start noticing details you used to miss-the way light falls on a face, the silence between lines, the color of a car. It doesn’t make you a better viewer-it makes you a more aware one.

Does semiotics apply to TV shows and streaming content too?

Yes, even more so. TV and streaming rely heavily on visual shorthand-thumbnails, opening credits, recurring motifs-to keep viewers engaged across episodes. The color palette of Stranger Things, the recurring use of VHS distortion, the way characters are framed in Succession-all are semiotic choices designed to build mood, class, and tension over time. The same rules apply, just stretched across more episodes.

Why do some people say semiotics is "too academic"?

Because early semiotic analysis was dense and jargon-heavy. Terms like "paradigmatic axis" or "grand syntagmatique" made it feel inaccessible. But the core ideas are simple: signs carry meaning, and filmmakers choose them deliberately. You don’t need the jargon to use the tools. Just look. Listen. Ask why.

Can AI understand film semiotics?

AI can identify patterns-like color use or shot length-but it doesn’t understand cultural meaning. It can flag a red dress, but it won’t know if it symbolizes revolution, love, or danger without human context. That’s why AI-generated films often feel emotionally flat-they lack the lived, cultural weight behind signs. Semiotics is still a human skill.

Where to Go From Here

If you want to dig deeper, start with Daniel Chandler’s Semiotics: The Basics-clear, practical, and free online. Watch YouTube channels like "Every Frame a Painting"-they break down film signs in under five minutes. Re-watch your favorite movies, but this time, mute the sound. What do you still understand? That’s semiotics working. Now turn the sound on. What changes? That’s the full picture.Film doesn’t just tell stories. It whispers them. And once you learn to listen, you’ll never watch a movie the same way again.