When you watch a foreign film and the words appear at the bottom of the screen, you might think it’s just typing. But every comma, every pause, every word choice in those subtitles is a silent decision that can change the entire meaning of a scene. A joke might die. A threat might vanish. A moment of silence might become a scream. Subtitle translation isn’t about swapping words-it’s about rebuilding emotion, culture, and rhythm in another language.

Subtitles Don’t Translate Words, They Rebuild Experience

Take a classic scene from Pedro Almodóvar’s Todo Sobre Mi Madre. The line “No me digas que no te gusta la vida” literally means “Don’t tell me you don’t like life.” But in English subtitles, it often becomes “Don’t tell me you hate life.” Why? Because “no te gusta” in Spanish carries a softer, more emotional weight than the blunt English “hate.” The translator chose a stronger word to match the character’s dramatic tone. That one shift turns a quiet plea into a cry of despair. The original line is gentle. The translated one is thunder.

That’s the rule: subtitles don’t preserve meaning-they reconstruct it. You can’t fit every Spanish syllable into an English line. You can’t show a 12-second monologue in 5 seconds of screen time. So you cut. You simplify. You rephrase. And every cut changes the film’s soul.

The Hidden Rules of Subtitling

There are hard limits in subtitling. Most screens allow only two lines. Each line holds about 35-40 characters. That’s less than a tweet. And viewers read at about 160 words per minute. So if a character speaks 200 words in 10 seconds, you’re forced to drop 20% of what they say. That’s not editing-it’s erasing.

Here’s what gets sacrificed most:

- Cultural references: A joke about a Spanish TV host? Gone, unless you replace it with something the audience knows.

- Wordplay: Double meanings, puns, rhymes? Almost always lost. A French film where a character says “Je suis un homme” (I am a man) while holding a baby-implying he’s now responsible-becomes “I’m a dad” in English. The poetic ambiguity dies.

- Pauses and silences: In Japanese cinema, silence is a character. In English subtitles, silence is just blank space. You can’t subtitle a sigh.

Subtitlers don’t just translate-they decide what matters. And sometimes, what’s left out is more important than what’s left in.

How One Word Changes a Film’s Tone

Consider the Korean film Parasite. In the original, the chauffeur says to the wealthy son: “너는 나한테 뭐라고 해?” Literally: “What do you call me?” But the English subtitle reads: “What do you call me?” - identical. Yet the tone changes entirely.

In Korean, the phrase carries a quiet, dangerous edge. It’s not a question. It’s a challenge. The word “해” is informal, almost disrespectful. The English version sounds neutral. The power of the moment is muted. The translator chose clarity over tension. The audience loses the sense that this man is about to explode.

Compare that to the same film’s English dub. The line becomes: “You think you can talk to me like that?” Now it’s loud. Aggressive. But it’s not what the actor said. The original silence was more terrifying. Subtitles can’t capture that. Dubs can’t either. Neither version is wrong. But both are different films.

Regional Dialects and the Loss of Identity

When a character speaks with a regional accent or dialect, subtitles often flatten it into standard language. In La Grande Illusion, a French soldier from the south says, “C’est pas grave,” with a thick Provençal accent. In English, it becomes “It’s no big deal.” But the original carries class, region, and history. The accent says: “I’m not one of you.” The translation says: “I’m fine.”

Some translators try to preserve it. In the English subtitles of My Left Foot, the Irish working-class dialogue is kept raw: “I’m not askin’ for nothin’.” That’s rare. Most studios demand “clean” English. That means losing the texture of where people come from. A character from Naples becomes generic. A peasant from the Andes becomes just “a man.”

Language isn’t just words. It’s geography. It’s class. It’s history. Subtitles often erase all three.

The Art of the Untranslatable

Some words simply don’t exist in other languages. Japanese has “tsundere”-someone who acts cold but secretly cares. German has “Fernweh”-the ache to be somewhere you’ve never been. What do you do when a character says “Ich hab Fernweh” in a German film? Do you write “I miss home”? That’s wrong. Do you leave it as “Fernweh”? That’s confusing.

Most subtitlers pick the closest approximation: “I’m restless.” “I’m longing.” “I want to leave.” None are right. But one must be chosen. And the audience walks away with a simplified version of a feeling they’ve never felt before.

This is why watching foreign films with subtitles feels like peering through a fogged window. You see the shapes. You hear the voices. But the depth? The nuance? It’s filtered, softened, sometimes erased.

Who Decides What Goes In?

There’s no single rulebook. Subtitling is a mix of art, law, and compromise. Studios often hire translation agencies. Those agencies assign the work to freelancers who may never have seen the film before. One translator might be fluent in Mandarin but know nothing about 1970s Hong Kong gangster slang. Another might be a film student who loves poetry but doesn’t know how fast viewers read.

Some studios have in-house teams. Netflix has a global subtitling team with specialists for each language. They watch the film multiple times. They consult directors. They test subtitles with native audiences. But even then, trade-offs are constant.

Take Drive My Car, the Japanese Oscar winner. The film has long, quiet monologues. One scene runs 8 minutes. The English subtitles had to cut 40% of the dialogue. The director, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, approved it. He said: “It’s not my words anymore. It’s the film’s new voice.” That’s the reality. The translator becomes a co-director.

When Subtitles Change the Story

There are cases where subtitles didn’t just change tone-they changed plot.

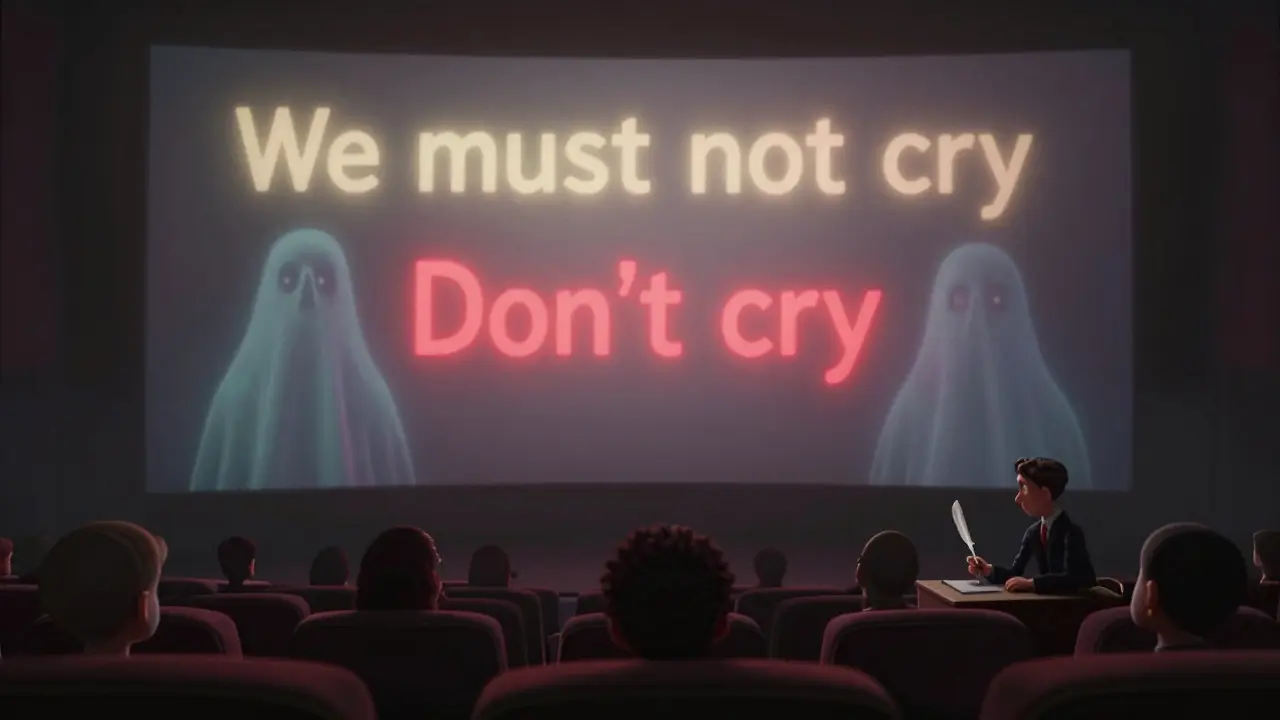

In the Italian film Life Is Beautiful, the father tells his son: “Questo è un gioco. Non dobbiamo piangere.” (“This is a game. We must not cry.”) In some English versions, it became: “This is a game. Don’t cry.” The difference? “We must not cry” implies shared strength. “Don’t cry” sounds like a command to a child. The first version turns the father into a protector who shares the lie. The second turns him into a manipulator.

The meaning shifted. The emotional core changed. And viewers walked away with a different understanding of the father’s sacrifice.

That’s not a mistake. That’s translation.

What You’re Really Watching

When you watch a subtitled film, you’re not watching the original. You’re watching a new version-a reinterpretation shaped by time, space, culture, and the translator’s choices. The actor’s voice, the director’s cut, the lighting-all are intact. But the words? They’ve been remade.

That’s why two people can watch the same film, one with subtitles, one without, and walk away with completely different impressions. One sees a quiet tragedy. The other sees a loud melodrama. Neither is wrong. But both are incomplete.

Subtitles are the invisible hand of cinema. They don’t just carry meaning-they create it. And every time you press “subtitles on,” you’re choosing which version of the film you want to see.

Why can’t subtitles just translate word-for-word?

Word-for-word translation doesn’t work because languages have different rhythms, grammar, and cultural context. A 10-second line in Japanese might need 20 seconds in English. Subtitles must fit on screen, be readable in under 3 seconds, and still carry emotion. That means cutting, rephrasing, and sometimes replacing entire phrases.

Do subtitles ruin the original meaning of films?

They don’t ruin it-they reshape it. Some meaning is lost, but new meaning can emerge. A translator might turn a subtle insult into a direct threat to match the actor’s tone. The original intent is preserved in spirit, even if the exact words change. It’s adaptation, not corruption.

Are subtitles better than dubbing?

Neither is better-they’re different. Dubbing replaces the actor’s voice, so you lose lip sync and vocal emotion. Subtitles keep the original voice but strip away some dialogue. Subtitles are preferred by cinephiles because they preserve the actor’s performance. Dubbing is often easier for casual viewers. The choice depends on what you value: authenticity or accessibility.

Can a bad subtitle change how I feel about a character?

Absolutely. A gentle line turned harsh, a poetic pause removed, or a cultural reference replaced with something generic can make a character seem cold, stupid, or cruel-when they were meant to be tender, wise, or complex. Subtitles shape perception more than most viewers realize.

Why do some films have better subtitles than others?

It comes down to resources and care. Big studios like Criterion or Netflix hire experienced translators who watch the film multiple times, consult directors, and test with audiences. Independent films often rely on volunteers or low-budget agencies. The difference shows in nuance, timing, and emotional accuracy.